History of the City of Ostrava

Under the Mythical Landek

Ostrava got its name from the river Ostravice, which divides the town into its Moravian and Silesian parts. The root of the word Ostrava, “ostrý”, means “sharply, quickly, swiftly flowing river“. The first evidence of human settlement in the region on which today's city lies goes back to the Stone Age. Approximately 25,000 years ago, mammoth hunters had an encampment at the top of Landek Hill, which has been evidenced by numerous archaeological finds. The most significant discovery was a 48 mm high figurine of a woman’s torso made from hematite found in 1953, called the Petrkovice (or Landek) Venus. Archaeologists have found evidence that prehistoric hunters used coal from exposed seams on the surface as fuel. It is the first evidence of the use of black coal in the world. In the 8th century, one of the numerous hill forts of the Slavic Holasic tribe was built on the legendary Landek Hill. The stone castle of Czech King Přemysl Otakar II was built here sometime in the middle of the 13th century.

Ostrava got its name from the river Ostravice, which divides the town into its Moravian and Silesian parts. The root of the word Ostrava, “ostrý”, means “sharply, quickly, swiftly flowing river“. The first evidence of human settlement in the region on which today's city lies goes back to the Stone Age. Approximately 25,000 years ago, mammoth hunters had an encampment at the top of Landek Hill, which has been evidenced by numerous archaeological finds. The most significant discovery was a 48 mm high figurine of a woman’s torso made from hematite found in 1953, called the Petrkovice (or Landek) Venus. Archaeologists have found evidence that prehistoric hunters used coal from exposed seams on the surface as fuel. It is the first evidence of the use of black coal in the world. In the 8th century, one of the numerous hill forts of the Slavic Holasic tribe was built on the legendary Landek Hill. The stone castle of Czech King Přemysl Otakar II was built here sometime in the middle of the 13th century.

Birth of the Medieval Town

Ostrava’s oldest roots go back to the Polish (now Silesian) village of Ostrava, which was mentioned in a document from Pope Gregory IX in 1229. There are written records dating from 1297 of the construction of the Silesian Ostrava Castle on the promontory above the confluence of the rivers Lučina and Ostravice to guard the border between the Polish and Bohemian states. Today’s Moravian Ostrava, whose name was first brought up in the will of the Olomouc bishop Bruno of Schauenburg in 1267, was definitively awarded town status by 1279. The newly built town became the centre for the Episcopal village in the vicinity. Its core is composed of a square-shaped square (today’s Masaryk Square). In 1362, King and Emperor Charles IV awarded the town the right to hold a 16-day annual market. The privilege meant greater prestige for Ostrava, thanks to which the town on the left bank of the Ostravice River was able to become a significant spot on the map for 14th century medieval market stall holders. The Hussite Wars did not affect the life of the town significantly. In 1438, the town was held a Hussite commander, Jan Čapek of Sány, for a short while, and then after him by the warrior Jan Talafús of Ostrov. From 1437, Moravian Ostrava was solidly incorporated under Hukvaldy rule, whose fortunes it shared till 1848.

Ostrava’s oldest roots go back to the Polish (now Silesian) village of Ostrava, which was mentioned in a document from Pope Gregory IX in 1229. There are written records dating from 1297 of the construction of the Silesian Ostrava Castle on the promontory above the confluence of the rivers Lučina and Ostravice to guard the border between the Polish and Bohemian states. Today’s Moravian Ostrava, whose name was first brought up in the will of the Olomouc bishop Bruno of Schauenburg in 1267, was definitively awarded town status by 1279. The newly built town became the centre for the Episcopal village in the vicinity. Its core is composed of a square-shaped square (today’s Masaryk Square). In 1362, King and Emperor Charles IV awarded the town the right to hold a 16-day annual market. The privilege meant greater prestige for Ostrava, thanks to which the town on the left bank of the Ostravice River was able to become a significant spot on the map for 14th century medieval market stall holders. The Hussite Wars did not affect the life of the town significantly. In 1438, the town was held a Hussite commander, Jan Čapek of Sány, for a short while, and then after him by the warrior Jan Talafús of Ostrov. From 1437, Moravian Ostrava was solidly incorporated under Hukvaldy rule, whose fortunes it shared till 1848.

Wars and Catastrophes Hampered Expansion

The only stone building in town besides the manor house (burgrave’s residence), was the Church of St. Wenceslas (first written reference 1297). The basic system of town walls was built from 1371 to 1376. Reference to the town hall building on today’s Masaryk Square was first mentioned in 1539. It has undergone several structural modifications and it took on its current appearance in 1859. Documented evidence of the little wooden Church of St. Catherine in the Hrabová district of Ostrava dates back to 1564. Ostrava’s status was strengthened in the first half of the 16th century thanks to the development of professional industries (especially woollen cloth manufacture, weaving and tailoring). Profitable fish farming became a significant element of the local economy. In 1533, the town purchased the village of Čertova Lhota (today's Mariánské Hory) and in 1555 it added Přívoz to its purchases as well. Aside from military campaigns, life in Moravian Ostrava was also adversely affected by natural disasters – floods and fires. The largest fire, in 1556, practically destroyed the homes on the square. Approximately half of the inhabitants died in 1625 as a result of plague. After the Thirty Years War, Moravian Ostrava was one of the most afflicted towns in the Czech lands. Ostrava was first occupied by Danish forces and from 1642 the Silesian side was occupied by the Swedes.

The only stone building in town besides the manor house (burgrave’s residence), was the Church of St. Wenceslas (first written reference 1297). The basic system of town walls was built from 1371 to 1376. Reference to the town hall building on today’s Masaryk Square was first mentioned in 1539. It has undergone several structural modifications and it took on its current appearance in 1859. Documented evidence of the little wooden Church of St. Catherine in the Hrabová district of Ostrava dates back to 1564. Ostrava’s status was strengthened in the first half of the 16th century thanks to the development of professional industries (especially woollen cloth manufacture, weaving and tailoring). Profitable fish farming became a significant element of the local economy. In 1533, the town purchased the village of Čertova Lhota (today's Mariánské Hory) and in 1555 it added Přívoz to its purchases as well. Aside from military campaigns, life in Moravian Ostrava was also adversely affected by natural disasters – floods and fires. The largest fire, in 1556, practically destroyed the homes on the square. Approximately half of the inhabitants died in 1625 as a result of plague. After the Thirty Years War, Moravian Ostrava was one of the most afflicted towns in the Czech lands. Ostrava was first occupied by Danish forces and from 1642 the Silesian side was occupied by the Swedes.

The Discovery of Coal and the Ironworks Turn the Wheel of History

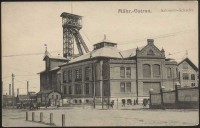

In 1763, the discovery of coal in the Burňa valley of Polish Ostrava resuscitated the economic life of the Ostrava region. Its abundance was confirmed four years later by mining expert Jan Jakub Lutz. Despite this fact, it was not until 1787 that the owner of the land, František Josef Count Wilczek, began regular mining there. The addition of Galicia to the monarchy in 1772 facilitated the expansion of trade in livestock and partly sparked economic development. A swift growth in agglomeration initiated the establishment of an ironworks in the village of Vítkovice in 1828 by the Olomouc Archbishop Rudolf Habsburský. A connection to the Ferdinand Northern Railway in 1847 through stations at Svinov and Přívoz enabled Ostrava to become, in the second half of the 19th century, one of the most significant industrial centres of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. The blossoming industry also called for an influx of people. Moravian Ostrava has just 2,000 inhabitants in 1830. Fifty years later the number of inhabitants was more than 13,000. The percentage of German and Polish speaking inhabitants significantly increased. The immigrants mainly settled down in worker colonies in Polish Ostrava, Vítkovice and other communities. The social and cultural life of the nationalities living in the town at the end of the 19th century was centred on the Czech National House (today’s Jiří Myron Theatre), German House (destroyed at the end of WWII), Polish House and Municipal Theatre (today’s Antonín Dvořák Theatre). The most significant church structure, the Cathedral of the Devine Saviour, was completed in 1889. After the birth of the Czechoslovak Republic in 1918, Ostrava retained its significant economic position thanks to its ironworks and mines and slowly transformed into an administrative, social and cultural centre.

In 1763, the discovery of coal in the Burňa valley of Polish Ostrava resuscitated the economic life of the Ostrava region. Its abundance was confirmed four years later by mining expert Jan Jakub Lutz. Despite this fact, it was not until 1787 that the owner of the land, František Josef Count Wilczek, began regular mining there. The addition of Galicia to the monarchy in 1772 facilitated the expansion of trade in livestock and partly sparked economic development. A swift growth in agglomeration initiated the establishment of an ironworks in the village of Vítkovice in 1828 by the Olomouc Archbishop Rudolf Habsburský. A connection to the Ferdinand Northern Railway in 1847 through stations at Svinov and Přívoz enabled Ostrava to become, in the second half of the 19th century, one of the most significant industrial centres of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. The blossoming industry also called for an influx of people. Moravian Ostrava has just 2,000 inhabitants in 1830. Fifty years later the number of inhabitants was more than 13,000. The percentage of German and Polish speaking inhabitants significantly increased. The immigrants mainly settled down in worker colonies in Polish Ostrava, Vítkovice and other communities. The social and cultural life of the nationalities living in the town at the end of the 19th century was centred on the Czech National House (today’s Jiří Myron Theatre), German House (destroyed at the end of WWII), Polish House and Municipal Theatre (today’s Antonín Dvořák Theatre). The most significant church structure, the Cathedral of the Devine Saviour, was completed in 1889. After the birth of the Czechoslovak Republic in 1918, Ostrava retained its significant economic position thanks to its ironworks and mines and slowly transformed into an administrative, social and cultural centre.

The Dream of a Greater Ostrava Fulfilled

On January 1, 1924, the so-called “Greater Ostrava” was formed. It merged seven Moravian villages into one greater whole (Moravian Ostrava, Přívoz, Mariánské Hory, Vítkovice, Hrabůvka, Nová Ves and Zábřeh nad Odrou). This significantly influenced the structural development of the town. A number of department stores, banks and administrative buildings sprang up. The greatest amount of attention was given to the ceremonial opening of the New Town Hall with its square 75 meter-high glass tower on October 28, 1930. Life in the town was significantly affected during the years 1929-1934 by the world economic crisis. After the Munich Agreement in the autumn of 1938 and its withdrawal from its borderlands with Germany, Masaryk’s Czechoslovakia experienced the tragedy of the Nazi occupation of the rest of the republic on March 15, 1939. Units of Germany’s wehrmacht had already marched into Moravian Ostrava a day earlier. The largest industrial enterprises, like Vítkovice Mining and Iron Corporation and the Ferdinand Northern Railway, came under the administration of the German Reich’s Herman Göring Werke concern and were refocused toward war manufacturing. Near the end of the war in August 1944, bombing attacks by Anglo-American allies seriously damaged the town. Ostrava and its inhabitants waited till April 30, 1945 to see liberation. The armed forces of the 4th Ukrainian Front of the Red Army and the 1st Czechoslovak Independent Tank Brigade thus engaged in heavy and bloody combat during the Ostrava-Opava operations.

On January 1, 1924, the so-called “Greater Ostrava” was formed. It merged seven Moravian villages into one greater whole (Moravian Ostrava, Přívoz, Mariánské Hory, Vítkovice, Hrabůvka, Nová Ves and Zábřeh nad Odrou). This significantly influenced the structural development of the town. A number of department stores, banks and administrative buildings sprang up. The greatest amount of attention was given to the ceremonial opening of the New Town Hall with its square 75 meter-high glass tower on October 28, 1930. Life in the town was significantly affected during the years 1929-1934 by the world economic crisis. After the Munich Agreement in the autumn of 1938 and its withdrawal from its borderlands with Germany, Masaryk’s Czechoslovakia experienced the tragedy of the Nazi occupation of the rest of the republic on March 15, 1939. Units of Germany’s wehrmacht had already marched into Moravian Ostrava a day earlier. The largest industrial enterprises, like Vítkovice Mining and Iron Corporation and the Ferdinand Northern Railway, came under the administration of the German Reich’s Herman Göring Werke concern and were refocused toward war manufacturing. Near the end of the war in August 1944, bombing attacks by Anglo-American allies seriously damaged the town. Ostrava and its inhabitants waited till April 30, 1945 to see liberation. The armed forces of the 4th Ukrainian Front of the Red Army and the 1st Czechoslovak Independent Tank Brigade thus engaged in heavy and bloody combat during the Ostrava-Opava operations.

Steel Heart of the Republic

After 1945 and through the 1950s, Czechoslovakia concentrated on the development of mining, the steel industry and other areas of heavy industry. Ostrava became its centre, becoming that period’s “city of coal and iron” and also the “steel heart of the republic”. In 1949, construction was started on the vast Nová Huť industrial complex in Ostrava-Kunčice. Massive support of heavy industry meant an inflow of new workers to Ostrava and its vicinity. Many new neighbourhoods grew up in the peripheral quarters of the town at that time, primarily Poruba, Zábřeh, Hrabůvka, and later Výškovice and Dubina. In 1945, Ostrava became the home for the Mining University (moved from Příbram) and for a branch of the Faculty of Education of Brno’s Masaryk University. The latter become independent in 1959 and in 1991 it became part of the newly established University of Ostrava. Cultural and social life were supported by two permanent theatres, today’s Antonín Dvořák Theatre (from 1945 the Provincial Theatre, 1949-1990 the Zdeněk Nejedlý Theatre) and Jiří Myron Theatre (formerly the Czech National House, 1945-1954 the Folk Theatre). Very popular theatres, especially among young theatregoers, are today’s Petr Bezruč Theatre (established in 1948 as the Youth Theatre) and the Chamber Theatre Aréna (formerly known as the Music Theatre from 1951). An amateur puppet theatre by the name of Wooden Kingdom was opened in 1946 for younger audiences, which was later renamed the professional Puppet Theatre in 1953. In 1954, today’s Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra Ostrava began putting on its concert performances.

After 1945 and through the 1950s, Czechoslovakia concentrated on the development of mining, the steel industry and other areas of heavy industry. Ostrava became its centre, becoming that period’s “city of coal and iron” and also the “steel heart of the republic”. In 1949, construction was started on the vast Nová Huť industrial complex in Ostrava-Kunčice. Massive support of heavy industry meant an inflow of new workers to Ostrava and its vicinity. Many new neighbourhoods grew up in the peripheral quarters of the town at that time, primarily Poruba, Zábřeh, Hrabůvka, and later Výškovice and Dubina. In 1945, Ostrava became the home for the Mining University (moved from Příbram) and for a branch of the Faculty of Education of Brno’s Masaryk University. The latter become independent in 1959 and in 1991 it became part of the newly established University of Ostrava. Cultural and social life were supported by two permanent theatres, today’s Antonín Dvořák Theatre (from 1945 the Provincial Theatre, 1949-1990 the Zdeněk Nejedlý Theatre) and Jiří Myron Theatre (formerly the Czech National House, 1945-1954 the Folk Theatre). Very popular theatres, especially among young theatregoers, are today’s Petr Bezruč Theatre (established in 1948 as the Youth Theatre) and the Chamber Theatre Aréna (formerly known as the Music Theatre from 1951). An amateur puppet theatre by the name of Wooden Kingdom was opened in 1946 for younger audiences, which was later renamed the professional Puppet Theatre in 1953. In 1954, today’s Janáček Philharmonic Orchestra Ostrava began putting on its concert performances.

On the Road to Freedom and Democracy

Considerable political and economic changes came after 1989. Ostrava became a statutory city lead by a city mayor, city council and by representation elected in free and democratic elections. As a consequence of industrial restructuring, mining activities were curtailed in a penetrative manner. The last car of coal was brought up on June 30, 1994 from the Odra shaft in Přívoz (formerly known as the František mine), which concluded more than two centuries of a continuous history of active mining enterprise in Ostrava. The Vítkovice blast furnaces, which are a conspicuous dominant feature of the city, were turned off in 1998. Vítkovice then began concentrating on machine engineering. The steel industry in the town was then centred in Nová Huť (now Arcelor Mittal). On May 30, 1996, the diocese of Ostrava and Opava was founded by the bull Ad Christifidelium spirituali by Pope John Paul II. The then-Basilica of the Devine Saviour was elevated to the status of cathedral. The Flood of July 1997, known as a “thousand-year flood”, dramatically affected the lives of the city and many of its inhabitants. The damage caused by the most extensive flooding in Ostrava’s history was estimated at more than CZK four billion. In 2000, Ostrava became the administrative centre of the newly established Ostrava Region, today’s Moravian-Silesian Region.

Considerable political and economic changes came after 1989. Ostrava became a statutory city lead by a city mayor, city council and by representation elected in free and democratic elections. As a consequence of industrial restructuring, mining activities were curtailed in a penetrative manner. The last car of coal was brought up on June 30, 1994 from the Odra shaft in Přívoz (formerly known as the František mine), which concluded more than two centuries of a continuous history of active mining enterprise in Ostrava. The Vítkovice blast furnaces, which are a conspicuous dominant feature of the city, were turned off in 1998. Vítkovice then began concentrating on machine engineering. The steel industry in the town was then centred in Nová Huť (now Arcelor Mittal). On May 30, 1996, the diocese of Ostrava and Opava was founded by the bull Ad Christifidelium spirituali by Pope John Paul II. The then-Basilica of the Devine Saviour was elevated to the status of cathedral. The Flood of July 1997, known as a “thousand-year flood”, dramatically affected the lives of the city and many of its inhabitants. The damage caused by the most extensive flooding in Ostrava’s history was estimated at more than CZK four billion. In 2000, Ostrava became the administrative centre of the newly established Ostrava Region, today’s Moravian-Silesian Region.